Let’s face it - “vibe coding” (using AI to assist with writing code) has already become a reality for many developers. Used carefully, it’s an efficient productivity tool. But as automation becomes embedded in our workflows, we risk a kind of AI automation complacency - the subtle drop in vigilance that happens when we start trusting the machine a little too much.

The speed and abstraction of letting a tool write your code make it harder to maintain a true understanding of what’s happening under the hood. And when you’re reviewing code written by an AI agent rather than your own, it’s easy to miss vulnerabilities that would normally stand out.

We learned that lesson the hard way when one of our vibe-coded honeypots introduced a subtle vulnerability of its own. What we found was both a fascinating and uncomfortable insight into the security impact of AI.

Vibe Coding a Honeypot

To deliver Intruder’s Rapid Response service, we have started using our own honeypots to catch emerging exploits in the wild and use them to write automated checks that protect our customers. Public vulnerability reports rarely come with details on how an exploit works, and in the early stages of a vulnerability’s lifecycle - when such information is only known by a small group of attackers - having a real example of someone using the vulnerability can provide crucial details. This helps us write robust detections that don’t rely on the system exposing its version number.

To support this goal, we built a low-interaction honeypot that can be rapidly deployed to simulate any web application and log requests that matched specific patterns for analysis. We couldn’t find an open-source project that quite met our needs, so naturally, we vibe coded a proof-of-concept honeypot using AI 😊. Our vibe-coded honeypots were deployed as ‘vulnerable infrastructure’ in environments where compromise is assumed (i.e. not connected to any sensitive Intruder tech) - but we still took a brief look at the code for security considerations before it went live.

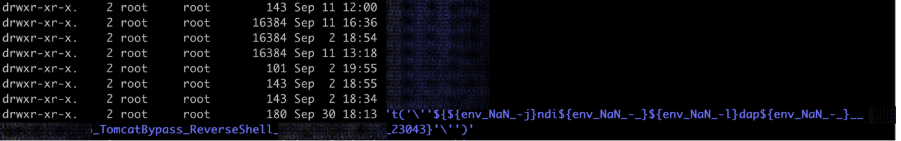

After testing it out for a few weeks, we noticed something odd – some of the logs, which should have been saved in directories named after the attacker’s IP address, were being saved with a name that was definitely not an IP address:

The Vulnerability We Didn’t Expect

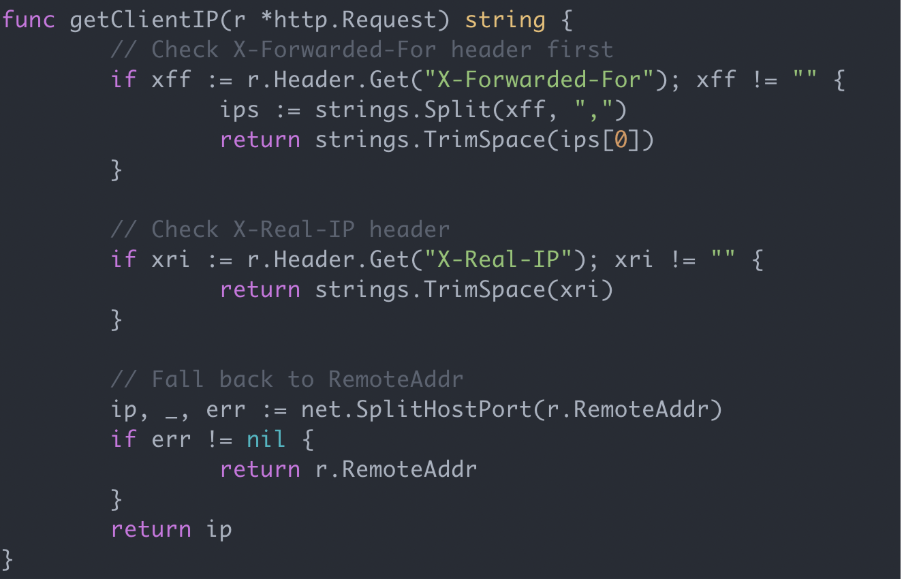

Seeing this kind of payload in a filename obviously rang alarm bells, as it suggested user input was being used in a place where we expected trusted data. After taking another look at the AI-generated code, we found the following:

An astute pentester or developer should notice the problem right away. The issue wasn’t even poorly documented behaviour of the Go API, or anything like that – it was explicit behaviour (and even nicely commented!). How did we miss this?!

The code takes the X-Forwarded-For and X-Real-IP headers from the visitor’s request and uses those as the IP address where present. These headers are intended for use where you have a front-end proxy between your user and your web server, so that you use the real visitor IP and not your proxy IP – but if using them, you must make sure you only trust them if sent from your trusted proxy! These headers are client-controlled data and are therefore an easy injection point for attackers. The site visitor can easily spoof their IP address or exploit an injection weakness using these headers as the attack vector – this is a common vulnerability we often find when pentesting.

In this case, the payload the attacker was using was being inserted into this header, hence our unusual directory name. Though there wasn’t any major impact here, and there was no sign of a full exploit chain, the attacker did gain some control over the program’s execution, and it wasn’t far off being much worse. If we had been using the IP address in another manner, it could easily have led to vulnerabilities like Local File Disclosure or SSRF.

What About SAST and Code Review?

Could static code analysis tools have helped here? We ran both Semgrep OSS and Gosec on the code, and neither reported this issue, though Semgrep did find other potential issues in the code. Detecting this vulnerability isn’t easy for a static scanner, as it’s a contextual problem. A taint checking rule could (and some scanners probably do) detect the use of the headers in the filename, but automatically deciding whether it has been made safe with an allowlist is a difficult problem.

So why didn’t a seasoned penetration tester notice it during the code review step in the first place? We think the answer is AI Automation Complacency.

AI Automation Complacency

The airline industry has long been aware of a concept known as Automation Complacency reducing vigilance of pilots – in other words, it is much harder for us to monitor an automated process without making mistakes than it is to avoid making mistakes ourselves when actively engaged in a task. This is exactly what happened here during the code review step when reviewing the AI-written code. The human mind inherently wants to be as efficient as possible, and when automation appears to ‘just work’, it’s much easier to fall into a false sense of security and relax a little too much.

There’s one key difference between vibe coding and the airline industry though – the lack of rigorous safety testing. Where pilots may get a little too relaxed and let the autopilot take the wheel, they have many years of safety testing and improvement to fall back on. This is not true for AI written code in the current climate, as it’s still very immature as an industry. Security vulnerabilities are just one quick merge away from production, and only a keen-eyed code review is in its way.

Not an Isolated Incident

For any readers thinking this was possibly a fluke and wouldn’t happen often – it's unfortunately not the first time we’ve seen this happen. We have used the Gemini reasoning model to help generate custom IAM roles for an AWS cloud environment that were vulnerable to privilege escalation. Even when prompted, the AI model responds with the classic “You’re absolutely right...” and then proceeds to once again post another vulnerable role. We had to iterate through improved custom IAM roles four times before the agent produced a setup that wasn’t vulnerable to allowing users with our new role to turn themselves into a Global Admin and take over the entire AWS account, and that was only after we both noticed the problem and coached it towards a solution. There was no indication from the agent whatsoever that there was a problem, and the initial role did provide the permissions that it needed to for the original task.

With a security engineer at the helm that’s ready to scrutinize the model carefully, many of these issues will get caught. But vibe coding is opening up these tasks to those with much less security knowledge. A recent piece of research looked at purpose-built platforms which use AI to write code and deploy it. They found thousands of vulnerabilities. At a minimum, we do not recommend allowing ordinary users (i.e. non-developers or security professionals) to use these types of platforms.

As we demonstrated in this post though, that’s potentially the least of your worries, because even developers and security professionals can make these mistakes. Ordinary end-users have no way to identify if the platforms they are using have been written with AI-assistance, so the burden falls upon the organization producing the product to ensure its security. If your organization allows developers to use AI to help write code, it is certainly time to look at your code review policy and CI/CD SAST detection capabilities to avoid falling foul of this new threat.

In our opinion, it’s only a matter of time before we start seeing AI-generated vulnerabilities proliferate. It takes a transparent organization to talk about their vulnerabilities, and even fewer are going to admit that the source of the weakness was their use of AI, so this problem is likely already widespread. This won’t be the last you hear of this, of that much we’re sure!