News of leaked API keys and the breaches that follow have been commonplace lately. So why is it that these secret, sensitive tokens seem to be getting so easily leaked or exposed?

We recently reviewed our own secrets detection capabilities, and did a deep dive into the types of secret exposures that traditional vulnerability scanners can detect. We developed a novel secrets detection method, and what we found was astonishing. This project revealed that there is a major class of leaked secrets weakness that is not being handled sufficiently by existing tooling - especially when it comes to secrets used by single-page applications.

We discovered and reported a plethora of critically sensitive secrets exposed by application front-ends. This included hundreds of Github API keys (some with full repository access), tokens providing us access to private ticketing systems, and lots more, such as secrets giving us the ability to post messages to private Slack channels.

Traditional Secrets Detection Methods

The traditional fully automated method for detecting application secrets hiding in plain sight is to search through a list of known common locations, and use a regular expression to match known secret formats. Whilst this method offers value and can be used to find some secrets that get accidentally exposed, it has serious limitations and won’t catch all types of exposures - particularly those which require spidering.

Let's take a look at the GitLab personal token template from Nuclei as an example to see why this is the case. Bear in mind, this is not a limitation of Nuclei, it is a limitation of large scale infrastructure scanning common to all VM platforms:

If we give Nuclei the URL “https://portal.intruder.io” the template will execute the following:

- Make a HTTP GET request to https://portal.intruder.io

- Read the direct response to this single request, ignoring any other pages/files including resources such as JS files (important for later).

- Attempt to identify the pattern of a GitLab personal access token

- If successful, make a follow up request to ascertain if the token is active via GitLab.com’s public API.

- If active, raise an issue

Whilst this typical usage is generally effective, and especially so when the template defines paths where secrets are commonly exposed, it will not detect secrets stored in JavaScript bundles. Nuclei gets fed the base URL of an application (e.g. https://portal.intruder.io and not https://portal.intruder.io/assets/index-DzChsIZu.js, where the secret resides). This is an important distinction as the JavaScript file(s) that powers the web application contains the developer’s custom code, and therefore is one of the most likely places an exposed token could be found.

What About DAST and SAST?

There are some Dynamic Application Security Testing (DAST) scanners out there which can spider applications looking for secrets in a more robust manner than the traditional non-spidering method above. However, this is a more expensive type of scanning which needs in-depth configuration and tends to be reserved for a few select applications run by the business. Additionally, we have not come across many DAST scanners which implement a wide range of secrets regular expressions, compared to secrets-specific scanners like Trufflehog.

You may also be thinking “Aha! But my Static Application Security Testing (SAST) scanner has me covered!”. And you are partially right - that SAST methods are a primary way to detect secrets in code and prevent exposures. But unfortunately they do not cover the whole picture, and we will detail an example below which would not have been caught by a SAST scanner.

Do Secrets Really Get Bundled in JavaScript?

When we embarked on this project we had significant doubts as to how common this problem would be. Are secrets really getting bundled into a JavaScript front-end, and is this really common enough to need an automated solution?

There was historical success within the team’s pentesting experience, however, and we knew this issue does happen. So we set out to see how we could leverage Nuclei with full automation to scan large numbers of targets at speed, without needing to configure a DAST scanner and fully spider applications.

Nuclei offers support for several types of protocols for templates including the JavaScript protocol which enables us to write templates with complex flows that just aren’t possible with standard yaml functions. For example, check out this template we helped build for the ToolShell weakness.

Implementing a simple spider within a single template was relatively straightforward. The first step was to make an HTTP request to the base URL of the target, scrape for javascript files embedded in the HTML, then store that list in a variable for future use within the template:

http:

- method: GET

path:

- "{{BaseURL}}"

extractors:

- type: regex

name: js_files

part: body

group: 1

regex:

- 'src=\"([^"]*\.js)\"'

internal: true

From here, we need a conditional step that will only run if one or more JavaScript file locations were captured. Then subsequent requests would make sure the files exist, then finally request the JS file and initiate the logic to match against a list of secrets regexes:

const pathInfo = normalizePath(jsFile);

if (!pathInfo) {

continue;

}

if (!visitedPaths.has(pathInfo.key)) {

visitedPaths.add(pathInfo.key);

set("js_path", pathInfo.original);

http(2) && http(3);

}

}

}

So in short, we used the JavaScript protocol to spider JavaScript files.

We included some extra logic to handle the following conditions:

- Not revisiting JavaScript files in case they are referenced twice (from our testing, it does happen, people do some weird stuff)

- Remove some common libraries based on their name, such as jQuery. We don’t need to test these libraries as they will be static, and we want to save scanning time.

The result is a template that can scan at speed and at scale, and identify token exposures. The only limiting factor left was the quality of the regexes that detect secrets.

An example of a problematic regex is one we found for Google Oauth tokens:

- type: regex

name: google_oauth

regex:

- (ya29.[0-9A-Za-z-_]+)

part: body

In this state, it causes a large number of false positives due to how lax it is and how JS is minified when deployed to live sites. We pulled a wide range of secrets regexes from various sources known to us, and got to work cleaning them up so we can deliver a fully automated check that’s low on noise and high on confidence.

Sensitive Secrets in the Wild

Okay so now for the fun part! We performed a large scale scan of approximately 5 million applications using our new JS bundle secrets scanner - let’s take a look at the kind of exposures we found. We identified a large number of exposures, way more than we had anticipated. The results file was over 100mb of plain text which included over 42,000 tokens to look at, across 334 types of secrets. We didn’t get a chance to look at them all, but among the ones we did triage, we identified some incredibly damaging exposures.

Code Repository Tokens

The most impactful exposures we found were tokens for code repository applications such as GitHub/GitLab. We identified a total of 688 tokens, many of which were still active. Yep - full access to repositories 💀.

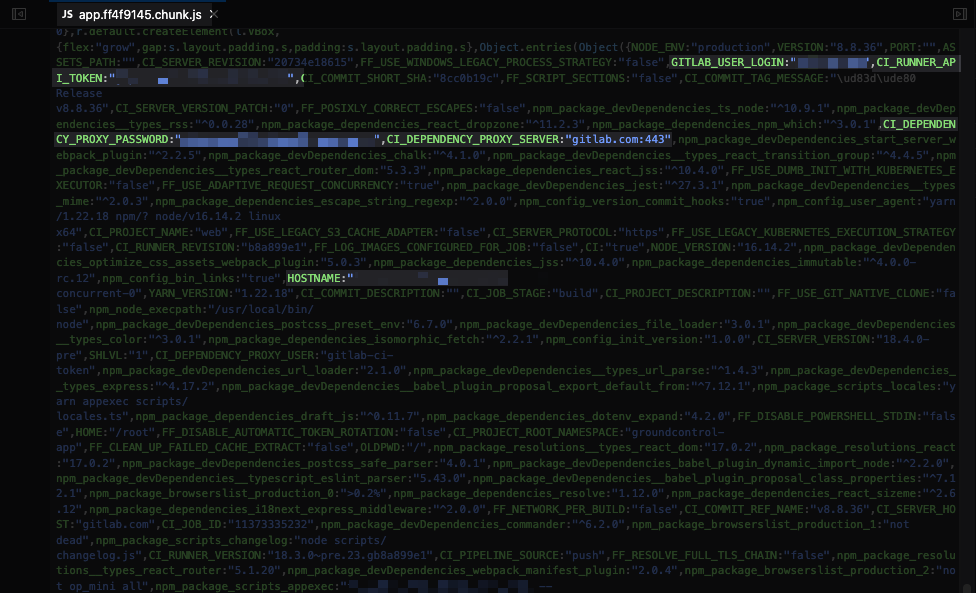

For example, we found this GitLab token embedded in a JavaScript file:

This token was a GitLab personal access token, but was scoped to allow access to all private repositories of a company. This included items such as CI/CD pipeline secrets for onward services such as AWS and SSH. It goes without saying really, but to be able to go from a simple JavaScript file scan and pivot into an AWS environment is mind-blowing.

After reporting this to the affected business we had a quick discussion to understand what caused the exposure. Huge credit to the contact here, both for being responsive and remediating the problem but also for their openness to discuss it with us. The issue for them was caused via their build process where they used a custom NodeJS build script that injects values where required. The fatal mistake they made was to use the process.env variable, which included all environmental variables instead of the ones within the .env file as intended.

Project Management API Keys

Another impactful exposure we identified was a Linear API key. Linear is a project management application aimed at software developers. Linear includes a GraphQL API that users can use to programmatically perform tasks.

As with the previous example, the token was laying right there within the JavaScript file:

In this case, it didn’t seem to be environment variables added during application build. It looks like the developers made the fatal mistake of committing a secret to the codebase. While looking at the code around the token, it looked as if they had added a feedback functionality to their application where users could create an issue within Linear directly via the front-end. This seems like a nice idea to streamline bug reporting, but doing it this way exposed their whole Linear instance to anyone who visited the page. Internal tickets, projects and links to downstream services and SaaS products were all exposed.

This one would likely have been caught by a good SAST scanner, but redundancy is still a good thing - especially redundancy that’s low cost and effective. It can’t hurt to flag this type of issue to your VM team, rather than relying on the devops teams having their SAST scanners configured correctly.

And Lots More…

These two examples aside, we identified a broad range of other tokens secrets, including:

- CAD Software API - Ability to view user data, metadata of files and projects, and download CAD files for buildings (including a hospital)

- Link Shorteners - Can create new links, and read already created ones

- Email Senders and Newsletter Management - Ability to extract all user emails who are signed up to active email campaigns or newsletters, ability to see campaigns and content

- Webhooks for various chat or automation platforms (all active), 213 Slack, 2 Microsoft Teams, 1 Discord, 98 Zapier

- PDF Convertors - SaaS products for tasks such as converting a website into a PDF

- Company Analytics/Contact Information - Products that scrape LinkedIn and other sources to collate information about companies for use by Sales and Marketing teams.

Conclusion

In recent years, we have seen an increase in available tooling and awareness to implement secrets scanning, especially earlier in the development cycle (shifting left). These protections offer significant value, such as SAST scanning, failsafes within code repository applications such as GitHub, and third-party tools providing guardrails to developers within IDE’s. But as you can see from this article, this is demonstrably not perfect! Shifting left certainly has its place, but secrets detection appears to be one of those areas that benefits from being hit from all angles, including robust remote scanning that leaves no stone unturned.

The key takeaway from this research for us was discovering the avenue that isn’t covered by traditional tools and processes, whereby secrets can be exposed via build processes that happen long after the classic shift-left failsafes have run. Looking forward, the prevalence of AI automation will only make this problem worse. We’ve shown that AI writes vulnerable code and makes mistakes just like humans do. And it looks like this problem is just beginning, with examples like this one starting to crop up, where AI dumps secrets in places it shouldn’t.

This is where implementing single-page application spidering checks within a vulnerability scanning application such as Intruder excels, so you can be sure secrets detection is getting the attention it deserves.

Our improved secrets detection checks are available to Enterprise plan customers. Book some time with us to learn more.